Liza Prangishvili

Illegal but legitimate

Women all over France go out during the day and sometimes at night to put up self-made information posters regarding femicide, the extreme crimes against women that take their lives for fact that they are women. They sometimes use explicit forms of expression to shock the public, which can result in their being arrested, or at times groups of men come to destroy their work and silence them.

Since 2018 especially, there has been a significant rise in femicide cases and from 2016 to 2019 there was an increase of almost 30 femicide cases annually, from 118 in 2016, to 146 in 2019. According to LeMonde and to a survey conducted by the French government, in 2019, 43% of femicide victims had previously filed a complaint to the police against the man who ultimately killed them, with no further action taken by the police.

In January 2020 a 44-year-old woman was killed by her ex-husband, even though she had been to the police 22 times, saying she was frightened for her life. Their response had been: “Don’t bother coming back a 23rd time”, according to TV France24.

Femicide is often overlooked by media, and if it were not for web pages like nous.toutes.org or Collages Feminicides, which are Instagram-based, many of these tragic killings would go unnoticed and silenced. Since 2018 many militant women all over France have taken matters into their own hands, creating Twitter and Instagram accounts to keep track of the femicide numbers.

Marie, a woman in charge of the Collages Femicides Twitter account, said that the goal of the movement is to someday stop having to count their dead. Collages Feminicides was created in August 2019 by Marguerite Stern, who went out into the streets of Marseille and plastered posters about femicide victims and the statistics describing the crimes. The movement grew quickly into a national movement. Today, the Instagram account @Collages_Feminicides_Paris numbers over 81,000 followers and has spawned many smaller accounts in other French cities.

Alena Ams and Garance F, two law faculty students from Chevreuse, created an Instagram account to bring the movement to their small city in 2020. Gathering over 200 people, they started pasting their self-made posters and informative leaflets around their city with messages such as “protect your daughters”, “educate your sons”.

Alena Ams and Garance F, two law faculty students from Chevreuse, created an Instagram account to bring the movement to their small city in 2020. Gathering over 200 people, they started pasting their self-made posters and informative leaflets around their city with messages such as “protect your daughters”, “educate your sons”.

“We were very careful where we put our collages. It’s a small city and we didn’t want any trouble. We chose free display panels and asked City Hall beforehand. Putting up posters on free display panels is legal, contrary to pasting posters around the city on posts or walls,” Ams said. In France there are special rules concerning “affichage sauvage”, or unauthorized public bill boarding. The website of the French Senate’s Minister for Spatial Planning and the Environment affirmed the following: “Uncontrolled bill boarding is a major source of visual pollution of our landscapes. Regardless of its content, this type of advertising is punishable under Article L. 581-29 of the Environment Code, which empowers the mayor or the prefect to order the immediate removal of such advertising.”

However, in spite of the necessary precautions and preparations, they had trouble. “We stuck them onto the display panel during the day and later that day they were already removed,” she says. Once they hadn’t been able to finish putting up their poster in the official free display panel when they were interrupted by a police officer. Garance F said a girl had contacted the Instagram account asking to put up a collage for her. Eight years before, when she was a child she was raped. She wanted her aggressor to know that she wasn’t afraid anymore, and asked them to write “8 years ago you raped me and ruined my life, but I’m not scared anymore, you should be.” Garence said the police officer told them that the message was “radical propaganda”. “We were shocked that he was more worried about a legal collage than the fact that a child got raped and that the person who did it is running free.” The women’s collective received a warning letter from the Police a few days later, telling them to stop their activity.

According to Garance, she had personally asked the Mayor if she and her colleagues could express themselves on the municipal panels reserved for posters. Thus it was not illegal and the Mayor was not the one who asked for it to be removed. The police officer from Paris, who was asked a question about this law and why they also take down/prohibit posters that are legal like the one Garance put up, didn’t have an answer. A French police officer stated, “I only follow Orders and the Law. When we see people putting up posters when there is a specific law prohibiting it, we act accordingly. We either warn them or fine them. The sanction depends on their behaviour. If they start to argue they will get a 68 Euro fine.”

Tamta Muradashvili, a Georgian lawyer specializing in freedom of speech, said that the police officer clearly violated the women’s right to freedom of speech. What Garance and Alena were doing was a matter of public interest, since they were defending vulnerable women. As for the poster, Muradashvili pointed out that even if it was explicit and a little shocking or disturbing for society, there is a landmark case of ECHR (European Court of Human Rights) supporting the freedom of expression. In that landmark case, Handyside vs. United Kingdom, the Court established the principle that “freedom of expression…is applicable not only to ‘information’ or ‘ideas’ that are favorably received or regarded as inoffensive or as a matter of indifference, but also to those that offend, shock or disturb the State or any sector of the population.” Therefore, if the goal of the feminists was to show the real face of violence, it might be necessary to use explicit forms of expression,” Muradashvili said.

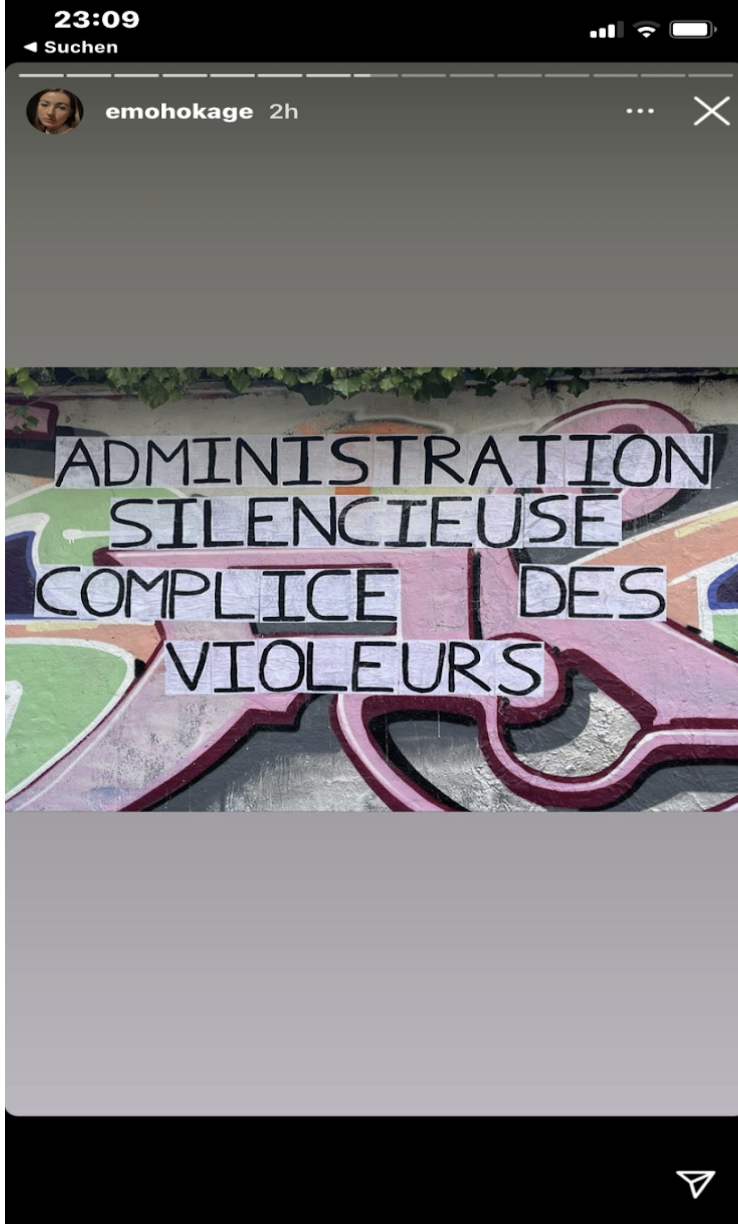

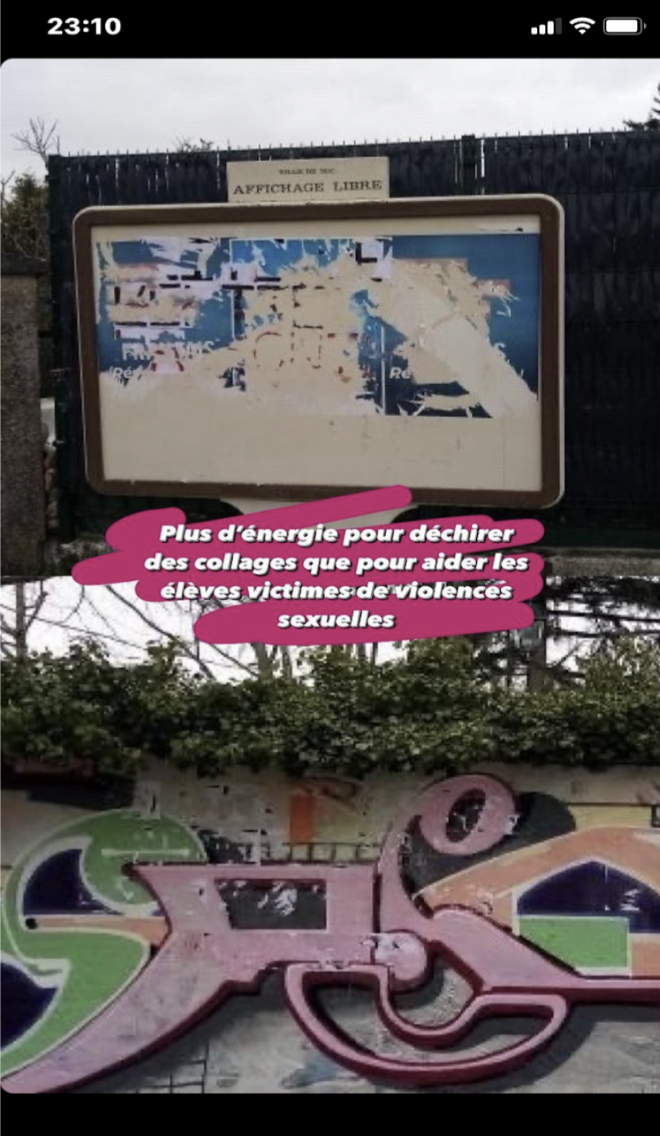

In March that year, Alena put up posters and a note on the legal billboards in front of her old high school, the Lycée Franco Allemand de Buc, with the help of other girls who either attended the school or had studied there in the past, to denounce the school’s administration inaction concerning student complaints regarding sexual abuse at the school. However, although this action was totally legal, even before classes began the next morning, the administration had taken down the posters, thus “violating their freedom of speech, silencing them”, said Alena on her Instagram Account. According to her, “The administration has more energy for tearing down posters than for helping victims of sexual abuse at their school,” where students are supposed to be and feel safe.

“Silent Administration accomplice of the rapists.” The second photo shows the torn-down posters from the graffiti walls and legal billboards.

Since this incident, many (former) students at this school have come forward, anonymously sharing their sexual assault stories that happened at the school; some expressed their fear of returning to the school where they would see their aggressors. Many women became furious that they were being silenced and that victims were forgotten, as if nothing was wrong. They have protested online through various radio and TV shows. “We will not stop. We live in a system where the police put more energy into removing posters than catching sexual predators and keeping women safe,” said Chloe Madesta, one of the founders of Collages Feminicides, to the French program, RMCBFM TV in 2019. Since the beginning of the Collages Feminicides Paris in 2019, 286 women have been killed, according to NousToutesOrg.