by Sopho Apriamashvili

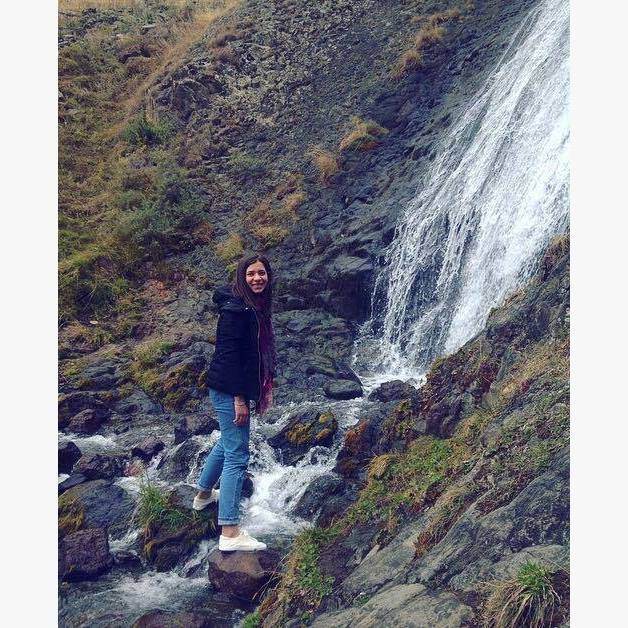

Nata Bolkvadze was 16 when she committed suicide at her home in the Guria region village of Natanebi on August 15, 2018.

Nata Bolkvadze was 16 when she committed suicide at her home in the Guria region village of Natanebi on August 15, 2018.

Her death was blamed on sexual cyber harassment by 22-year-old Mevlud Teziashvili, who she never met in person.

For almost one year Teziashvili and Bolkvadze were chatting on social media, which became known only in her suicide note to her mother.

“I was chatting with one guy, his name is Giorgi. We got very close. We even talked about future, even about a baby, but then I understood he was not who I thought he was. His friend was writing to me from his Facebook account. He told me he would screen shoot and send it to my (mother) and daddy if I would not do what he wanted. I could not stand it and I agreed. He forced me to take a lot of disgusting (sexual) videos and made me send them. Then he began to blackmail me with those videos. No one will understand what I went through during these days.”

The note was used as evidence in court, and this portion was published by Georgian media.

Her mother, 42-year-old Tamuna Dzneladze, says she has never read the full note.

A cousin, Lado Kviloria, says Bolvadze was deceived by Teziashvili from the beginning as the social media account of the defendant was fake:

“Teziashvili used the account with the name of Giorgi Tsertsvadze. He had photos of a boy whose name is not Giorgi and who was in jail at that time. This person Giorgi Tsertsvadze, does not really exist (there are some accounts with real Giorgi Tsertsvadzes, but they are not connected with Teziashvili). He made this up.”

Kviloria said this Facebook account had almost 4,500 friends, mostly girls.

It cannot be found now under this name.

Family members say the victim had a very positive personality and good relationships with her family.

But during the one-year relationship with Teziashvili, she never mentioned any trouble with a boy.

The day before the tragedy was a birthday for the victim's mother.

She remembers that her daughter wrote a congratulatory Facebook public post:

“… I want to see your eyes for a very long time… The eyes, which are full of kindness, sweetness and love. Let the God give you a long life… I love you the most, mommy, and I am the happiest person because I have you!”

“I had no concerns about her being in trouble. How could I notice it when she was trying so hard to hide it?" her mother says.

“I had no concerns about her being in trouble. How could I notice it when she was trying so hard to hide it?" her mother says.

Dzneladze assumes the reason for her daughter`s suicide was the feeling of shame.

“She had very good relationships with every family member, she could talk to everyone anytime, not only with me because I was her mother, but she had excellent relationships with her father, too. But she thought that talking about this was a shame for her. The only thing which I am mad at is that she knew there was nothing (she could do) that her family would not accept... Maybe I am guilty because I taught her too much openness. I see my guilt in it; I do not know…”

People in the village describes the family as very kind, friendly, educated and calm, and who had strong relationships with each other:

“I have never heard something bad about them,” says Zura Kharaishvili, a driver of one of the two mini-buses, which goes to the regional center Orzugeti from the village every day.

Three days after her death, police arrested Teziashvili in Tbilisi.

The investigation continues under Article 115 and under the first paragraph of Article 141.

The first involves bringing the victim to suicide;

the second is a derogatory act against a minor.

In Georgian legislation there is no law about sexual harassment. But Parliament has approved the first reading of a bill stating “undesirable sexual behaviors in public places, aiming at and/or causing abuse of dignity and creating a terrifying, hostile, humiliating or offensive environment for a person, will be punished with administrative fine.”

Teziashvili's former lawyer, Vazha Nebieridze, talked about what he said in the first few hours after he was arrested. Nebieridze accepted responsibility, but said he was just trying to have fun:

“I asked him if there was any pressure from police. He said there wasn't, and that when he found out that the girl committed suicide, he was waiting for his arrest. I do not know what he was planning for the future, but when I asked him why was he doing this, he answered that he was just having fun."

Nebieridze wouldn't say why she quit representing Teziashvili. According to the NATIONAL STUDY ON VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN 2017 conducted by European Union for Georgia, GeoStat, and UN Women, violence is a common experience in many women`s lives in Georgia:

Nebieridze wouldn't say why she quit representing Teziashvili. According to the NATIONAL STUDY ON VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN 2017 conducted by European Union for Georgia, GeoStat, and UN Women, violence is a common experience in many women`s lives in Georgia:

“one in seven women aged 15-64 reported that they have experienced physical, sexual and/or emotional violence by an intimate partner in their lifetime.”

According to the report, “overall, 26 percent of women reported having experienced sexual violence and/or sexual harassment by a non-partner, including sexual abuse as a child.” The report states that “close to half of all women (42 percent) and men (50 percent) agree with the statement that if a woman does not physically fight back, you cannot call it rape.”

22 percent of mean and 14 percent of women say that if a woman is raped, she has usually done something careless to put herself in that situation.

Even though Bolkvadze and Teziashvili never met in person, the act of blackmailing and demanding the pictures, which included sexual content of a 16-year-old girl, is considered as depraved behavior, which is a crime according to Georgian legislation.

There is no exact definition in Georgian legislation, but according to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), demanding sex-related photos and blackmailing the person with them is called cyber harassment:

“Sex-related extortion on the Internet, sometimes known as “sextortion”, is becoming increasingly common,” according to the UNDOC report “Study on the Effects of New Information Technologies on the Abuse and Exploitation of Children”.

“In such cases, offenders use information and photos, including collected through online contact with the victim, to blackmail minors into producing sexually explicit content or meeting them for sexual purposes, sometimes even threatening victims and their families. Offenders may send harassing messages or even threats via e-mail, instant message, social media profiles or other simple forms of electronic communication.”

There is no specific EU law on cyber bullying, cyber stalking and cyber harassment, but some aspects are covered, including expressions of sexual harassment of a victim under 18.

The EU is also funding programs to prevent violence against women, and young people, including online.

The United States has several different responses to these problems.

Some state legislatures have passed separate statutes specifically addressing harassment that occurs online.

Virginia, for example, directly addresses harassment that occurs on the internet, making it illegal to communicate via a computer network obscene language, threats of illegal or immoral acts, and obscene suggestions. A conviction can result in a restraining order, probation, or criminal penalties against the assailant, including jail.